With coronavirus challenging our sense of security, we naturally feel a loss of control. When we fear for the safety of loved ones, and even when our basic routines are disrupted, we are reminded of the delicate nature of what we consider familiar.

As with most things we can’t control, there isn’t much we can do now except wait for it to pass—and as we fulfill our foremost obligation to socially distance, this wait can feel frustratingly passive. But if we have an opportunity to actively contribute to another critical pandemic concern, why not take it?

Coronavirus has provided us leverage to secure our footing in eco-friendly living with a momentum we have perhaps never had. We have demonstrated the selfless ability to mutually forego consumer pleasures and adapt to a tightened environmental footprint when it counts. We’ve done the hard part when it comes to greenifying: starting. Let’s kick our conscious commitment up a notch, and piggyback off this energy to keep it going in times of stability.

Now’s the Time to Build Green Habits

Since these lockdowns started, there has been a global shift not only in CO2 emissions associated with the temporary friction on spending and travel, but also in our attitudes toward what we need and want, use and waste. We haven’t all proclaimed with sudden clarity that a life of minimalism is the way forward, but we have begun to look at our resources through a different lens, assigning more value to what we have.

Despite the tremendous amounts of farm-level food waste that has resulted from closures in the hospitality business, a shift in consumer mindset is, in my book, a huge environmental win. We have the capability to carry this mindset with us into the future, long past the chaos of this crisis.

The power of combined action is evident in China, where rates of coronavirus have dwindled; a trend soon to be followed in the US. Peaking death tolls provide evidence of our collective elasticity and our ability to put others before ourselves. When we emerge from our shelter-in-place mindset, I dearly hope that we continue to recognize the presence of excess in our lives, and the social, environmental, and spiritual benefits of rising above it.

Most techniques for green living are highly applicable now, in our time of obligatory self-sufficiency. If you can, get in the habit of buying your soaps, shampoos, and cleaning agents in bulk (or make them yourself!). Don’t rely on a constantly-replenishing supply of paper towels and tissues, but replace yours with cloth napkins and handkerchiefs. If you have a yard or even space for planters, grow your own vegetables and herbs. Conserve your resources by treating them with care, using only what you need, and reusing what you can. Learn DIY skills to make and fix, reducing your reliance on having to buy and replace.

We can fight lifestyle simplifications, or take them in stride; hate them, or have fun with them. Rather than thinking of our temporarily compromised lifestyle as restricted, think of it as focused. Eco-friendly living is not limited—rather, it is guided.

Environmental progress spurred by coronavirus can perhaps lend some purpose to what can otherwise feel like meaningless devastation. If we neglect to build on this progress, the feeling of futility that has paralyzed individuals for decades will continue to prevail: we need to quash this debilitating doubt by doing what we now know we can—making lasting repairs to our planet, one home at a time.

The Pitfalls of Constant Availability

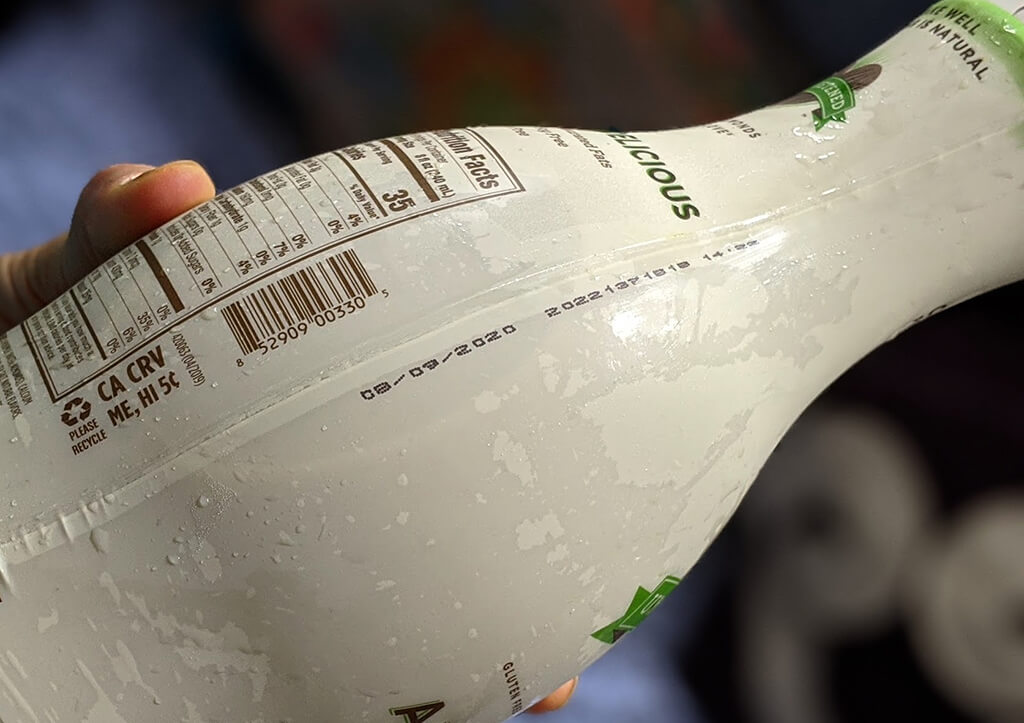

In 2020, we live lives of instant gratification. If we need a specific ingredient to cook with, our local supermarket is likely to have it at any given time, down to that niche product and specific brand; if we don’t feel like stepping out the door to do our shopping, we order it online. Buying was never easier.

When it comes to shopping for food, our expectations for bottomless availability is leading us down an environmentally-destructive path. I spoke in March with my former manager, Lauren Palumbo, about food waste at grocery stores; Lauren is the Chief Operating Officer at Lovin’ Spoonfuls, a Boston-based nonprofit that diverts food from the waste stream, redirecting over 16,000,000 pounds of excess food from retailers to food-insecure communities to date.

To meet consumer demand, grocery stores “over-order, overstock, and are always prepared because they don’t want to lose that customer,” says Lauren. “As recently as 40 or 50 years ago, that just would not have been the case. But I live in New England and it’s March, and I can get pretty much anything at the grocery store that I want, whether it’s coming from down the street or halfway across the world.”

This supposed progress has led our food system in a dire direction. “It is just not a system that allows for clear predictability about what consumers buy,” Lauren says. What consumers don’t buy ends up in our waste stream, contributing to that statistic you may be familiar with—the 40% of food that is never eaten. This means the massive amount of resources that go into growing, processing, packaging, transporting, storing, marketing, and selling almost half of our food (food that could provide valuable nutrition to those who have difficulty accessing it) are pointlessly depleted.

We have accepted this constant availability of supply as a fact of our consumer culture, something we are entitled to. The idea that it is a relatively recent evolution of our lifestyle is something we should continue to remind ourselves: as we are seeing during this pandemic, such consumer convenience is not automatic. Despite the reliance we have developed upon this system of excess, we can clearly exist with a reduced version of it.

In fact, in order to advance our food system in a way that fits sustainably with our lives as mortals dependent on the wellbeing of our planet, we will need to move away from it. To do so, “it would take a really significant shift in the way that we think about how we produce and order and secure our food as consumers,” says Lauren. “I think as long as we as consumers understand that we want high quality and we want things to be available all the time, we are driving that problem. And I don’t think food is the only place where that happens. If you look at a Marshalls or a TJ Maxx or something like that, it’s happening there for the exact same reason as it does with food, it’s happening with retail in a different format.”

During this time, when our lives have turned sideways and we adjust to new ways of consuming, we are given an opportunity to re-evaluate what it costs to sustain our system of supply, and what drives our level of demand. We can learn from the crisis we face right now and, aided by this perspective, equip ourselves to prioritize environmental health.

Push Forward

The unfortunate reality is that we need the extremity of a pandemic to spur us to environmental action: the extremity of our warming planet is too abstract for us to feel. If we can collectively choose to take our impending environmental emergency as seriously as we take an emergency that is undeniably upon us, we will be able to keep it from becoming the kind of tragedy that we are currently experiencing.

Inaction is largely a product of doubting the importance of our contributions: though our culture has entertained a steady crawl in the right direction, an unacceptable majority of us have yielded to this feeling of powerlessness. Not unlike the battle that consumes us now, the state of our earth leaves no more room for procrastination. We now have proof that when we buckle down and do our part, our individual actions can contribute to beating a global catastrophe.

Essentially, all we have to do in our fight against climate change is expand upon and integrate isolation-friendly habits of moderation into the flow of our regular lives, tweaking them to fit feasibly into the long-term.

Sustaining a reduced footprint doesn’t have to be as uncomfortable as the shock of our suddenly-imposed isolation: environmental diligence isn’t a grueling, time-consuming slog. Once you develop personalized systems to support your modified routines, you will question how you have lived otherwise.

Continue to take ownership of your role as members of society and our ecosystem. Harness this momentum.

Related:

An Imperfect Food System: It All Comes Back to Climate Change

How to Shop Responsibly (and Buy Less Stuff)

Captive Overconsumers: Why We’re Stuck in a Cycle of Spending

by Yenny Martin